CHAPTER 4: 1819-1829

In 1819, Virginia and the rest of the United States experienced their first major economic depression, known as the Panic of 1819, affecting every industry and aspect of society with widespread ruin. The roots of the Panic occurred in 1816. The British Empire had engaged in war on two continents; with the United States in the War of 1812, and with France in the Napoleonic Wars. As these wars came to a close, the volcanic eruption of Mount Tambora was having a dramatic effect on the climate of northern Europe, drastically affecting their crops, reducing their food supply and ushering in widespread illness. British soldiers returning from war were faced with high unemployment, inflation on basic commodities and deplorable weather. British industry, especially the textile mills which employed hundreds of thousands, was suffering from a lack of available cotton.

In an effort to alleviate the constriction of food and supplies, British authorities removed the customs duty tax on American produce in order to purchase as much grain as the United States could supply. The demand was high and the supply limited, which caused the price of wheat, corn, and other grains and farm produce to escalate to record breaking prices for the next two years. In addition, British authorities needed to keep the country’s factories operational to prevent economic collapse in the midst of this calamity. Factories focused on producing cheap exports which were readily purchased in the growing American markets. The British textile industry survived on raw cotton, which was greatly diminished everywhere except America. As a result, cotton prices surged.

Interestingly, while the British removed their duty on American goods, the United States government increased the tariffs on all imports from England to spite the British recovery as punishment for causing The War of 1812. It was noted in the Carthage Gazette in April of 1816, “Britain will not look on it [the tariffs] with indifference. She has played successful the game of crowns and at the game of commerce she is adept not to be foiled even by the cunning hucksters [politicians] of New England.” Oh how prophetic these words became, as England would have a checkmate on America, in the game of commerce, in the years to come.

These were boom years for American merchants, farmers and plantation owners. Cotton had climbed from 7 ½ ¢ per pound in 1812, to 34 ¢ in 1818; and tobacco had more than doubled from 4 ¢ per pound in 1814, to 9 ¢ in 1818. As prices for produce soared, farmers desired to purchase more land to increase their yield. The banks began overextending themselves, offering loans beyond their financial backing. Land values surged in certain areas form $2 per acre to over $100 per acre during the height of the frenzy. And even at that price, planters and speculators were still able to turn a profit during the boom years. Land speculation became epidemic.

Since gold and silver were particularly rare during this era in American history, banks were allowed to print their own paper money. These bills were redeemable for “specie,” meaning gold or silver, upon request of the holder at the bank. Originally, the banks held gold and silver reserves to equal the amount of the value of paper money printed and distributed; however, over time, banks began to over print and distribute more bills than were backed by specie held in their bank. In addition, since every State and locality had different paper money, the value of that currency in trade decreased the further the distance from the bill’s origin bank. Dollar bills from a bank in New York might trade for 80 cents in Virginia, and vise versa; whereas, a dollar bill originating from a bank in Williamsburg, Virginia, might trade for 95 cents in Richmond, Virginia, and vice versa. Paper bank notes further destabilized as early as July of 1817, when banks, merchants and taverns in Washington City (Washington D.C.) began declining payment with any foreign banknotes beyond its state borders, except notes from the Bank of The United States and its branches.

The United States government established the 2nd Bank of the United States in an effort to standardize currency and hold its value backed by specie, however, it too fell into corruption during the boom years and over printed its paper money beyond what was backed in precious metals reserves, making paper money truly valueless. A final undermining of bank note value occurred throughout 1818, when the 2nd Bank of the United States began accumulating and sending overseas vast amounts of specie from all available banks in order to repay the twelve million dollars in bonds that had become due from the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

What no one anticipated was how the eventual and inevitable recovery of the European harvest yields would affect every aspect of the American economy. In the spring of 1818, European crops recovered, and after two years of paying exorbitant amounts on American produce and cotton, British Parliament played a checkmate in the game of commerce by reinstating Corn Laws, which denied the import of foreign grains into the country. American wheat would plummet from $2.50 per bushel to 70 cents per bushel over the following years. In addition, English textile mills ceased buying American cotton in an effort to reduce its inflated price and began to purchase a lesser quality cotton from India. This sent the price of cotton from 34 ¢ per pound in 1818 to 17 ¢ by 1820, eventually bottoming out at 9 ¢ in 1823. The impact of these changes was a crushing blow to the booming American markets.

However, word from abroad traveled slowly during this time. Americans received all overseas news from port newspaper reporters interviewing transatlantic passengers debarking ships. Any information gained was typically further verified by the overseas newspapers also carried onboard, before being printed in the American papers. In addition, within the United States, local information was also delayed, as postal letter and word-of-mouth were the only means of transmission from place to place before the coming of the telegraph in the 1840s. Tragically, as the markets of the eastern States were collapsing, the uninformed western planters, farmers, businessmen, speculators, and commission merchants were still buying goods, cotton and land at record high prices. On June 12, 1819, the Huntsville Alabama Republican newspaper, reported that in the east “extraordinary pressures in the mercantile part of that community” had begun moving west and south “until the whole union [had] become embarrassed by the failures of mercantile houses and the depreciation of the paper currency.”

Merchants, planters, farmers and speculators who had bought goods and land on credit, unexpectedly and abruptly became hopelessly in debt and would have to liquidate all their assets to repay their creditors. During this time there were no exemption laws, thus all possessions a person or business owned were subject to be sold to satisfy his debt, generally causing total ruin to the owner. The creditor, if unsatisfied in his personal collection efforts, would force collection of the debt through the courts via lawsuits. However, if still unsuccessful, there was another more dreaded means of at least partial collection. “Shavers,” made a business of purchasing delinquent credit notes at a discount, and then forcing full collection, by the sheriff, who would hold a public auction of some or all of the debtor’s property needed to satisfy his debt.

During the Panic of 1819, Virginia was unique among the states in its splendid efforts in rendering aid to the impoverished. Cities, like Richmond, were hit especially hard by poverty and its effects were highly noticeable compared to the rural areas. In an effort to quell the homelessness, poor houses were established throughout the city. On November 7, 1821, Royal’s brother Samuel Shepherd (1792-1849) and his business partners William Pollard (?-?) and Thomas Ritchie (1778-1854), were paid $3.25 by the county for the print work they had done in advertising the building of a poor house.

Although churches had always rendered care for the poor, the Commonwealth of Virginia created a system of support in 1780. That year, the Virginia General Assembly established the Overseers of the Poor, being a group of qualified men from each community elected to render support to their local poor. One of their main functions was legally binding abandoned or impoverished children to good families to receive an education and/or learn a vocation until the age of 21 years old. In June of 1819, as the United States plummeted into the depression, the Henrico County Court appointed Royal F. Shepherd, John S. Ellis and William B. Price as Overseers of the Poor for the Upper River District.

Royal F. Shepherd fulfilled the purpose of his position well, and his care of the poor is well documented within the minute books of Henrico County. One example that is particularly interesting occurred in early 1822. John Halestock, Tom Halestock and Jesse Halestock were three orphaned free boys of colour found in the Upper River District of Henrico County. After the Overseers of the Poor bound two of the boys to good families, Royal F. Shepherd took a personal interest in last child’s wellbeing. On February 2, 1822, Royal was legally bound to Jesse Halestock until the youth reached the age of 21 years old. It is unknown what became of these three brothers, however, despite the circumstances in their youth, they were clearly presented with a significant opportunity to flourish. Royal F. Shepherd held his position as Overseer of the Poor until his resignation on June 4, 1822. The justices then appointed Royal’s friend John F. Henley in his place.

While Royal was graciously saving his fellow man in the Upper River District, a tragedy occurred at home. Circa 1819, Royal F. Shepherd’s wife Mary “Polly” (Cottrell) (1792-c.1819) died at 27 years of age. She was survived by her husband and two daughters, Mary A. Shepherd (c.1811-c.1833), age 8, and Elizabeth Shepherd (c.1815-c.1842), age 4. Mary’s death would have been almost unbearable for this young family. The Shepherd children had lost their mother and all the security, love and comfort only she could provide, and Royal had lost his companion in life.

During this time, the Shepherd household had four servants: one female between the age of 26 to 44 years, two females 14 to 25 years old, and one male 14 to 25 years old. In this family’s time of need, their ‘black family’ would have ascended to the occasion, assuming the roll of mother to the children and caretaker of the house for Mr. Shepherd. Although, Royal F. Shepherd, no doubt, developed a deep bond of appreciation towards his servants during this time of loss, he needed the security of a real mother for his daughters.

On April 11, 1820, Royal stabilized his household through a new marriage, this time to his cousin Mildred Shepherd (1800-c.1832). The bride was the 20 year-old daughter of the late Reuben Sheppard (1772-1813) and Sarah “Sally” Cocke (?-1822). Due to Mildred’s youthful age, her mother, as acting guardian, issued a letter of indemnification to the Henrico County Court to allow the matrimony. Interestingly, the merger of these two Shepherd families would have added financial security to benefit both sides. Royal clearly was achieving a comfortable life, having land, slaves and status; and records indicate that Mildred personally owned four male slaves, under the age of 14 years old, as well as, being an heir to her late father’s land and property. However, more than anything else, Mildred’s youth added considerable benefit to Royals’ legacy, as she would bear him five children throughout their marriage: Samuel D. Shepherd (1821-1896), Mosby Shepherd (c.1822-1841), Royal Fleming Shepherd, Jr. (1824-1863), William Shepherd (1826-?), and Jane Ann Shepherd (1828-1895).

Shortly after their marriage, Royal and his wife Mildred sold the 12 3/8 acres of land she had inherited from her late father’s estate. The property was located on Old House Branch and was bounded by the lands of Mildred’s brother and sister Robert Shepherd (1809-aft.1840), and Lucinda Shepherd (1807-1877), as well as, the lands of her cousin Stephen Duvall (1782-1850). The land was purchased on September 26, 1820, by Joseph Riddle for $100 current money of Virginia.

In January of 1821, Royal’s uncle Thomas Shoemaker (1757-1821), husband of the late Frances Shapard (c. 1763-c.1801), died in Henrico County. Thomas was a wealthy man, having notable holdings in land and slaves. His wife, Frances, had predeceased him, so his entire estate was distributed to his children Elizabeth Shoemaker (c.1782-?) who married Sherod H. Johnson in 1804; Holman Shoemaker (c.1784-1849) who married Elizabeth Ford in 1806; Price Shoemaker (1789-1842) who married Cynthia Patmon (1795-1857) in 1811; Sally Shoemaker (c. 1791-?) who married Richard Cocke in 1804; Samuel Shoemaker (c.1794-1819); Thomas M. Shoemaker (1796-1863) who married Elizabeth Patmon (1802-1845) in 1821; Royal Shoemaker (c.1797-1859); and Edwin Shoemaker (c.1800-1824) married Susannah West in 1824. His son Thomas M. Shoemaker was appointed the administrator of his father’s estate, with David A. Shepherd and Price Shoemaker as securities in the amount of $7,000.

In 1821, Royal F. Shepherd’s wife Mildred blessed him with the birth of his first son. The baby was given the name of Samuel David Shepherd (1821-1896), honoring not only Royal’s father, but his brothers Samuel Shepherd and David A. Shepherd as well.

On August 6,1821, Royal F. Shepherd was appointed as Constable of the Upper District of Henrico County for a term of two years. His cousin Stephen Duvall (1782-1850) and his brother David A. Shepherd (1795-c.1830) were bound as his surety in the amount of $1,500 for the faithful performance of his office. Recall that On December 8, 1812, during the War of 1812, Royal held this same office in Henrico County for two years. Approximately every month, Royal would submit a bill to the County Court, which in turn was forwarded to the Auditor of Public Accounts for payment. His billable compensation for services rendered ranged monthly from $1.60 to $6.64. Royal resigned from the office on May 5, 1823, and William Gill was appointed in his place. It is impressive that in 1821, at 32 years of age, Royal was a Constable, an Overseer of the Poor, a farmer, a husband, a father and a master.

Circa June of 1822, Royal’s aunt and new mother-in-law, Sarah “Sally” Sheppard (?-1822), widow of Reuben Sheppard (1772-1813), died in Henrico County. Royal F. Shepherd became the administrator of the estate and was backed by his cousin Stephen Duvall (1782-1850) as his surety in the amount of $2000. On August 21, 1822, Royal held an estate sale at the farm of the late Reuben and Sally Sheppard, where he and his wife purchased a loom, candlesticks, bread tray, blankets, table cloths, barrels, gun, hoes, cow, plow and gear. Items purchased by other buyers included a negro boy Peter, negro boy James, negro man Solomon, 4 cows, furniture, kitchenware, food, spinning wheels, tools, crop of fruit, crop of greens, crop of cotton, crop of oats, crop of wheat, etc. Purchasers were: Royal F. Shepherd, Reuben Shepherd, Jr., Stephen Duvall, Charles Nuttall, Benjamin Duvall, James H. Patterson, William Alley, James Longest, John S. Ellis, Thomas Shaw, John L. Bowles, Samuel Cottrell, Jr., Jordan Fares, Anderson Sharp, John Brown, Martin Pate, Samuel Flesher, Bartan Smoot, Samuel Brown, Charles Woodward, John F. Henley, Thomas Cocke, John Patterson and Royal Shoemaker.

The court had appointed John F. Henley, Charles Woodward, Jesse Sneed and Obadiah Duval as the appraisers of her estate. They were also to assign the value and portion of undivided land and slaves that each of the heirs would receive. After the sale of the undivided land for $691, the sale of one negro woman for $150 and the proceeds from the estate sale of $947, each of the eight legatees received $217.43 as their inheritable portion. Royal also received a commission as the administrator of the estate in the amount of $42.

Samuel Smith Cottrell (1782-1855), husband of Sarah W. Shepherd (1797-1855), was appointed as the guardian of the orphaned minors Reuben Shepherd (1803-1892), Richard C. Shepherd (c.1805-c.1842), Lucinda Shepherd (1807-1877) and Robert Shepherd (1809-aft.1840). The surety for Samuel S. Cottrell was James Patterson (c.1795-?), husband of Elizabeth Shepherd (1796-?), in the amount of $3000. At the distribution of the inheritance, Samuel S. Cottrell, as guardian of four of the Shepherd orphans, received $869.72 to be held in trust for the care and education of the children, until they reached the age of 21 years old.

Circa 1822, Royal F. Shepherd and his wife Mildred were blessed with the birth of their second son. They named the baby Mosby Shepherd (1822-1841).

In 1822, Royal F. Shepherd (1789-1849) had three slaves over the age of 16 years and four horses. His brother David A. Shepherd (1795-c.1830) had two slaves over the age of 16 years and four horses. David had his 80-acre country land near the coal pits in Henrico County, and also had acquired a city dwelling in Richmond on H Street. As an investment, David and his cousin Thomas M. Shoemaker (1796-1863) obtained two tenements of land in the city of Richmond, next to David’s residence, that they sold on August 9, 1822, for $1,900 to William Fulcher.

Thomas M. Shoemaker (1796-1863) was the son of Frances Shapard (c. 1763-c.1801) and Thomas Shoemaker (1760-1821), as well as, the cousin of David A. Shepherd. Interestingly, on August 6, 1821, Thomas M. Shoemaker married Elizabeth Patmon (1802-c.1845), the sister of David’s wife Nancy Patmon (1800-c.1823). In August of 1823, the court ordered Royal F. Shepherd, David A. Shepherd, Reuben Burton, Samuel Cottrell and John Lacy as commissioners to examine and settle all the accounts of Thomas M. Shoemaker as the executor of Thomas Shoemaker, deceased. After his legal responsibilities were concluded, Thomas M. Shoemaker and his wife Elizabeth moved to Shelby County, Kentucky; no doubt being influenced by the letters of Nancy Shepherd (1794-1873), daughter of Reuben Sheppard (1772-1813) and Sarah “Sally” Cocke (?-1822), and her husband Richardson Jones (1791-1878), who had settled in Shelby County in 1819. About a year after Thomas moved to Kentucky, his brothers Royal Shoemaker and Price Shoemaker (1789-1842) and Price’s wife Cynthia Patmon (1795-1857), sister of Thomas’ wife Elizabeth, also migrated to Shelby County. In the 1830s, the Jones family and Shoemaker families migrated together to Daviess County, Kentucky, where Thomas and his brother Royal settled on 252 acres along Panther Creek.

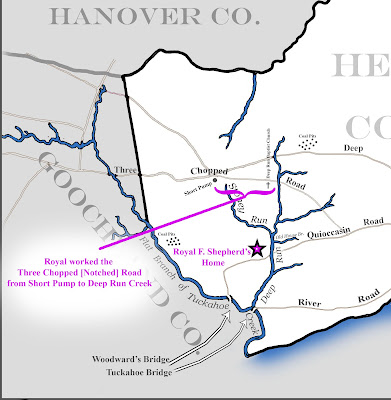

During this era, quality roads were crucial for travel by horse and wagon, as well as, for allowing planters to get their products to market in a timely manner. By law, roads were to be maintained twice a year by court selected landowners bordering the road. They were required to keep the road free of low hanging limbs, remove nuisance rocks, brush and stumps and make repairs as necessary, in an attempt to make travel safer. Most planters utilized their slaves for this labor. On May 6, 1822, The County Court ordered that the hands of Royal F. Shepherd, Richard Shepherd, Stephen Duval, Zacharia McGruder, Samuel Cottrell, Peter Fletcher, John Blackburn, Samuel Brown, Samuel Cottrell, Jr., and Charles Woodward be assigned to work on the Notched Road from the Short Pump to Deep Run, of which Royal F. Shepherd was appointed surveyor. Royal received $12 for the services he rendered in supervising the roadwork. On October 7, 1822, Royal’s brother David A. Shepherd was appointed surveyor of the road from Hungary Run to the Deep Run Coal Pits, in the place of John Lacy.

In August of 1823, Royal’s aunt Elizabeth Shapard (c.1755-1823) the wife of the late Joseph Duvall (?-1800) died in Henrico County. Her sons, Stephen Duvall (1782-1850), and Obadiah Duvall (1794-?) were the administrators of her estate, with Royal F. Shepherd and John L. Bowles as securities in the amount of $4,000. The County Court commissioned Royal F. Shepherd, John S. Ellis, Jesse Sneed, William Gill and Samuel Brown to settle the account of the administrators of Elizabeth’s estate and report their findings to the court.

Tax records for Henrico County, in 1824, documented that Royal F. Shepherd had three slaves over the age of 16 years, one male and two females. He also had five horses. His brother David A. Shepherd was taxed on two slaves over the age of 16 years and four horses. Their cousin Reuben Shepherd (1803-1892) and Richard C. Shepherd (c.1805-c.1842) were also accounted for on the record as white poles over the age of 16 years. Richard initially appeared in in the tax records in 1823, whereas, Reuben first appeared in 1820. Neither of them had slaves or horses at this time.

On May 5, 1824, Royal F. Shepherd acquired 40 additional acres of land adjoining his property on Deep Run. The land was sold by Charles Nuttall and his wife Maria Longest for the sum of $360. Charles and Maria were married in Henrico County on July 9, 1821. The property was also bounded by the lands of Samuel Cottrell and Samuel Brown.

Royal F. Shepherd and his wife Mildred were blessed with the birth of their third son on September 23, 1824. They named him Royal Fleming Shepherd, Jr. (1824-1863), in honor of his father.

David A. Shepherd and his brother-in-law Fleming Patmon were summoned to be jurors on numerous court cases in 1824. Fleming Patmon (c.1797-c.1849) married Sarah “Sally” Ryall, the daughter of John Ryall (1770-1809) and Mary Smith (?-?), on February 7, 1820. Fleming and David had a tremendous friendship throughout their lives, and were most likely business partners in coal mining or land specualtion. Both men had much in common, Fleming, like David was a slave holder, a staunch democrat and had a reckless entrepreneurial spirit. Fleming and his wife lived along the Richmond Turnpike and Old Coal Pit Road, near David Shepherd’s land. In March of 1822, Fleming was commissioned as Captain in the 33rd Regiment, 4th Division, 2nd Brigade Virginia Militia. In April of 1822, Fleming was appointed as Constable of Upper District of Henrico County, for a term of two years; however, he resigned his position in March of 1823. In the early 1830s, Fleming’s entrepreneurial ventures rendered him financially desperate. He was sued, in 1832, by Sherard H. Johnson, husband of Elizabeth Shoemaker (c.1782-?), for the recovery of a debt, upon which Fleming had bound his farm as collateral. On February 9, 1833, Fleming’s farm of 170 acres upon which he resided, seven miles from Richmond was sold at public auction. Pressed for funds, Fleming also sold off most of his negros, going from three slaves in 1830 to one slave by 1832. Interestingly, as a means of income, in June of 1834, Fleming was appointed as Constable, serving two full terms until 1838. In the 1840s, Fleming resided on 80 acres of land on Old Mountain Road, near his old farm. He died in 1849 in Henrico County.

David A. Shepherd had married Fleming Patmon’s sister Nancy in 1818. In or about the year 1824, Nancy died in Henrico County. She was survived by her husband and daughter Mary Elizabeth Shepherd born circa 1820. Fleming Patmon and his wife Sarah clearly played a significant roll in consoling and caring for David and his young daughter after the tragedy. Through this association, David was introduced to Sarah’s sister Nancy Apperson Ryall (1802-?). Apparently, the match was fruitful, as David A. Shepherd married Nancy A. Ryall circa 1825. David would have two additional children through this union, John David Shepherd (c.1826-c.1895) and Mary Jane Shepherd (c.1828-?).

Nancy Apperson Ryall (1802-?) was the daughter of John Ryall (1770-1809) and Mary Smith (?-?) and was named after her aunt Nancy (Ryall) Apperson. Nancy Apperson Ryall’s (1802-?) father John had died when she was only 6 years old, and it appears that their grandfather James Ryall (?-1812) and his wife Lucy became a source of security for the family. When James died in 1812, he left most of his estate in the form of land and slaves to his grandchildren Nancy and her five siblings, being Mary Jane Ryall who married George King on September 6, 1810; James Smith Ryall (1798-1882) who was a bachelor, John Bacon Ryall (1804-?) who married Maria Cottrell (1808-?) on May 25, 1827, the daughter of Peter Cottrell (1783-1827) (son of Peter Cottrell 1760-1815 and Susanna Shapard 1760-1807) and Sarah Ellis; Sarah Miller Ryall who married Fleming Patmon (c.1797-c.1849) on February 7, 1820; and Betsy Burton Ryall (1800-?) who married John P. White on October 7, 1817.

Interestingly, Nancy A. Ryall had a fair amount of wealth for a woman of her age. When her grandfather’s estate was settled in 1818, Nancy was bequeathed a slave girl named Keziah and had inherited 170 acres from the division of land. Upon receiving this property, she appointed John P. White as her guardian, and he gave bond in the sum of $3000. However, by 1819, Martin Smith had become her guardian. It appears that after Nancy and David A. Shepherd married, they resided on the 170 acres of land, making it their home.

On April 6, 1825, the justices of the County Court received a report from Jesse Snead, who was appointed to superintend the election of Overseers of the Poor in the Upper River District of Henrico County. According to the report, David A. Shepherd, Malachi Tinsley, and John S. Bowles were duly elected as Overseers of the Poor in the said district. The three men returned to court the following month where they were interviewed by the justices and qualified to commence their work.

On August 1, 1825, William Gill was appointed as the new surveyor of the road from Deep Run Church to Short Pump in the place of Royal F. Shepherd. Deep Run Church was located on Three Chopped Road, less than two miles from Royal’s plantation. The initial church was founded in 1742 as an Episcopal [Church of England] congregation, and a wooden church was built in 1749. During the American Revolution, favoritism towards Episcopal churches waned and the building was commissioned for use as a war hospital. After the war, a Baptist congregation assembled there, and, in 1791, it became known as Hungry Baptist Church. In 1819, church leaders changed its name to Deep Run Baptist Church, due to its proximity to the Deep Run Creek. It is known that some of Royal’s children joined the Third Baptist Church in Richmond Virginia in the early 1840s. And it is highly probable that the Shepherd family were members of the Deep Run congregation, illuminating their association with the Baptist denomination.

In 1826, Royal F. Shepherd had five slaves, three over 16 years of age and two between the ages of 12 to 16 years. He also had three horses. His brother David A. Shepherd had six slaves, four over the age of 16 years and two between the ages of 12 to 16 years, and four horses. Both men were living in the Upper District of Henrico County as their primary residence. Interestingly, their cousins, Richard C. Shepherd (c.1805-c.1842) and Reuben Shepherd (1803-1892), sons of Reuben Sheppard (1772-1813) and Sarah “Sally” Cocke (?-1822), had sporadically appeared in the Henrico County tax records throughout the 1820s; however, commencing in 1826, and thereafter, they are listed only in Goochland County. For the year 1826, Reuben was listed as having five slaves over the age of 12 years and one horse. His brother Richard had no slaves and one horse.

A celebration was had in 1826, in Henrico County, when Royal’s wife Mildred gave birth to their fourth son. They named the baby William Shepherd (c.1826-?).

Another grand celebration occurred, this time in Goochland County, when, on March 22, 1826, Reuben Shepherd (1803-1892) married Susan G. Jordan (c. 1809-1894). The bride was the seventeen year-old daughter of Reuben Jordan (1773-1826) and Phebe Wingfield (?-1839) who married in Goochland County, Virginia, in 1801. Her father owned a 500-acre plantation in Goochland County, and was the master of approximately 6 slaves. Her parents had eight children whom survived to adulthood: Robert W. Jordan (1802-1856); James B. Jordan; Susan G. Jordan (1809-1894) married Reuben Shepherd; Samuel M. Jordan; Reuben F. Jordan; Joseph W. Jordan; Sarah F. Jordan married Alfred Crump; and Phebe Ann Jordan married J.W. Walton. Tragically, only a few months after Reuben and Susan married, her father died in Goochland County. The young couple inherited a few slaves and a division of her father’s plantation where they initially resided.

During the late 1820s and early 1830s, Reuben began working towards owning and operating his own grist mill and needed the capital to fund such a venture. Over the following years, he would liquidate many of his assets to fund his business endeavor. In 1826, Reuben had five slaves over 12 years of age and one horse, of which, all would be sold over the next four years. Reuben would not invest in another slave until 1834. In 1827, Reuben sold the land that he inherited from his father Reuben Sheppard, Sr. (1772-1813), being 3/4 of an acre land in Henrico County on Deep Run and Old House Branch, for $50 to Stephen Duvall (1782-1850). In 1831, Reuben and Susan sold all their rights to her father’s estate for $450 to her brothers Robert W. Jordan and James B. Jordan.

In 1832, Reuben’s hard work and ambitious savings finally allowed him to realize his dream. On March 31st, he purchased, for $2000, a mill pond with houses and adjoining 10 acres on Tuckahoe Creek in Goochland County from Samuel Leake. He began grinding grist that same year, and his operation became known as Shepherd’s Mill. Over the following years, he purchased additional acres surrounding his mill from John W. Ford, Charles Ford and Benjamin Nuckols. In 1838, his mill was running a healthy profit and Reuben acquired three slaves and had recently purchased an additional 360 acres of land around the mill from John W. Ford for $1000, bounded by Chopped Road and a road leading to Shepherds Mill and Tuckahoe Creek.

However, in 1840, the effects of the economic depression known as the Panic of 1837, had fully reached Goochland County and Reuben found himself in troublesome debt. As early as October of 1837, Reuben and his brother Richard C. Shepherd (c.1805-c.1842), who likely worked together at Shepherd’s Mill, were the defendants in lawsuits filed against them for the recovery of debts. In an attempt to alleviate their financial woe, Reuben and his wife sold the land she inherited from her father on Tuckahoe Creek for $237 to her brother Robert Jordan. Reuben also sold 250 acres for $700, on March 1st to Robert Farrar, adjoining Three Notched Road, being the greater portion of land that he purchased in 1838 from John W. Ford. In June of 1840, Reuben made an agreement to sell at public auction his remining 148 acres on Tuckahoe Creek that included his grist mill if he was unable to satisfy his $669 debt to Charles Ford by December.

From all accounts, Reuben honored his debt to Mr. Ford and retained his mill for the duration of his life. His occupation was listed as a miller in 1870 and a miller and a farmer in 1880. However, he also continued to invest in real estate. At the beginning of the Civil War in 1860, Reuben purchased 65 acres of land known as Little Store for $640, upon which he sold three years later to Jacob Sampson for $1,170. In 1870, he sold 10 acres to Marie L. Watson for $350, being a portion of land from the division of the estate of Reuben’s late brother-in-law Joseph W. Jordan. In 1874, Reuben carved 8 acres from his land along the Three Chopped Road, adjoining the property of Dr. R. G. Parrish, and sold it to Andrew Johnson for $80.

Reuben died at his home on October 16, 1892 at the impressive age of 89 years old. He was a member of the Methodist Church and had favored the Republican Party. His wife Susan G. Shepherd survived him for two more years, passing away on September 9, 1894. Together they had eight children: Sarah A. Shepherd (1827-1900); Elizabeth “Betsy” Shepherd (1832-?); Susan E. Shepherd (1833-?); Lucinda F. Shepherd (1836-1861); Robert B. Shepherd (1840-1908); John W. Shepherd (1843-1923); Phebe J. Shepherd (1846-1913); and Mildred Shepherd (1852-1893).

Circa July of 1826, Royal F. Shepherd’s mother, Mary (Allen) (Sheppard) Cottrell (c.1769-1826) died in Henrico County. She had survived two husbands, Samuel Shapard III [spelled later as Sheppard] (c. 1767-1795) and Charles Waddell Cottrell (1751-1818). After the death of her last husband, Mary remained a widow, residing on her 300 acre estate, for the remainder of her life. Mary’s son Royal F. Shepherd and her step-son Samuel Cottrell became the executors of her estate. An estate sale was held on July 13, 1826 of the remaining personal property, collecting a sum of $1,285.95 to be distributed among the Shepherd and Cottrell heirs.

In the spring and summer of 1826, a new road was to be opened from the Tuckahoe Coal Pits, through the lands of John Wickham, to the James River Canal. The County Court commissioned Royal F. Shepherd, Jesse Sneed, Samuel Brown, John F. Henley and Samuel Cottrell to be appointed commissioners to view the ground along which the new road was proposed and report back their recommendations.

Henrico County was the site of the first commercial coal operation the history of the United States. Coal from the Richmond deposits was first discovered in the county in 1701, and was prized for its high quality. During the 1700s to the early-1800s, this coal was extracted by digging a hole or pit in the ground to a depth of about 30 feet, all the while carving out the coal from the walls, which began about four feet below the surface. The pit eventually filled with rain or ground water, whereby, a new pit was begun, abandoning the former. In the 1760s, Samuel DuVal became one of the first to excavate, transport and sell coal from the Deep Run area. With the labor of ten men, they removed the coal, placed it on wagons or boats and shipped it to Richmond, where it was further distributed for sale. Because of its high quality, Deep Run coal was favored by iron smiths to fuel their furnaces, and even fueled the Westham Foundry for weapon production during the Revolutionary War. In 1786, coal was discovered in the Tuckahoe Valley and landowners along the Tuckahoe Creek capitalized on the opportunity. William Cottrell, Thomas Randolph, John Ellis and John Wickham all had coal fields and shipped the product down the creek, to the James River, and then to market in Richmond.

During the War of 1812, the United States government placed tariffs on British imported coal which caused a shift favoring the number of American consumers purchasing local Virginia coal. As coal production increased, improvements were desperately needed to maintain the roads and waterways for transportation. Safer, wider and more maintained toll roads known as ‘turnpikes’ were constructed as the main coal roads, which could bear the weight of constant wagon flow. During this time the Deep Run Turnpike was constructed from the coal pits directly to Richmond. While these roads initially helped, the high tolls and wagon congestion proved them inadequate long term. Deep Run Creek was also dammed in an effort to maintain its water level to increase the predictability of shipping. In the late 1820s, the Tuckahoe Canal was built to allow easier access to the James River, reaching the Deep Run pits in 1829. During this time, on a larger scale, the James River Canal was being widened, straightened and rerouted to accommodate better water travel for shipping and transportation as part of Virginia infrastructure improvements that would continue through the 1850s.

In the 1810s, large scale coal mining operations began digging deeper and farther underground. In 1818, Henry “Harry” Heth’s mine in the Richmond field reached 300 feet in depth and was the first in the United States to incorporate the use of a steam powered pump to continually remove the ground water. In the mid-1830s, short-span railway systems would be built around the mines at Tuckahoe and Deep Run areas to transport coal with more ease. Although these larger mining operations became increasingly more dangerous due to fires, cave-ins, heavy machinery and poisonous gases, the profitability made mine owning or investing desirous. The profitability of Virginia coal would reach its pinnacle in 1824, holding 60 percent of the coal market. However, as railway systems to larger coal fields in other states, especially Pennsylvania, allowed for higher coal production, easier coal transportation and cheaper coal prices, Virginia coal declined drastically to about 10 percent of the market by 1840. After the Civil War, Virginia coal mining faded into obscurity.

In 1827, Royal Shepherd’s brother David A. Shepherd, of 32 years of age, had created a financially comfortable life for himself. He had 250 acres of land, five slaves and three horses and was in a business partnership with his friend and former brother-in-law, Fleming Patmon. Although it is unclear in what business the two men were involved as partners, it does seem to be linked to the coal industry, possibly as small-scale miners. It is very evident that as the Virginia coal market faltered in the late 1820s, so too did David and Flemings business venture. The first sign of their impending financial woe occurred on November 8, 1827, when Richardson Energy, a small-scale coal company, purchased for a measly $1, the mineral interests that David A. Shepherd and Fleming Patmon had in two tracts of land.

In January of 1828, the same year that Pennsylvania coal overtook Virginia coal in the U.S. market, David A. Shepherd found himself in debt to James P. Taylor in the sum of $217.97, for which he leveraged his negro boy Jesse, three work horses and one wagon and gear as security. Unfortunately, David was unable to pay the debt on time and on June 17th, these items were sold at public auction at Wilson Brackett’s tavern in the city of Richmond. In March of that year, David was $50 in debt to Mosby Woodson and was forced to secured his negro girl Causey to be sold at public auction to satisfy the debt. In April, David was $134.60 in debt to his brother Samuel Shepherd of Richmond, upon which David entered into an agreement that if the debt was not paid, his brother Royal F. Shepherd would sell David’s slave ‘Stephen’ at public auction and disperse the funds accordingly.

The financial ruin and stress felt by David A. Shepherd is evident in that his personal property diminished from five slaves and five horses in 1828, to one slave and two horses only a year later. During this time there were no exemption laws, thus all possessions a person or business owned were subject to be sold to satisfy his debt, generally causing total ruin to the owner. The creditor, if unsatisfied in his personal collection efforts, would force collection of the debt through the courts via lawsuits. However, if still unsuccessful, there was another more dreaded means of at least partial collection. “Shavers,” made a business of purchasing delinquent credit notes at a discount, and then forcing full collection, by the sheriff, who would hold a public auction of some or all of the debtor’s property needed to satisfy his debt.

In an effort to save his home from being taken in bankruptcy or by shavers, David A. Shepherd sold his 170 acres and all his household goods and furniture to his children for $1, on July 28, 1828, “for and in consideration of the natural love and affection which I bear to Mary E. Shepherd, John D. Shepherd and Mary Jane Shepherd…” In August, David sold the land upon which his coal field was likely located for $400 to David Baker. This was the 80 acres of land along the road leading to Burtons’ Coal Field, that he had purchased from Samuel Smith Cottrell in 1817, and was adjacent the lands owned by coalers John Lacy and Heth, Sheppard & Co. (being Harry Heth, Benjamin Sheppard, Robert Gordon and James Carrie). By 1829, David had become completely destitute of property, owning no land, slaves or horses, and he died in 1829 or early 1830, at 35 years of age, in the prime of his life. While David’s business collapse explains his financial demise, his early death creates a mystery. Another possibility was that David may have been badly injured or had an illness rendering him unable to work, thus setting off the chain of events that led to his financial ruin and early demise. Regardless of the cause, this tragic event was devastating to his older brothers Royal F. Shepherd and Samuel Shepherd, whom had all been so close.

After David’s death, his wife Nancy remained on their 170 acre farm in Henrico County, raising her one year old daughter Mary Jane Shepherd (1828-?), her three year old son John David Shepherd (1826-1895), and her nine year old stepdaughter Mary E. Shepherd (1820-?). Fortunately, Nancy’s sister Betsy Burton Ryall (1800-?), whom had married John P. White in 1817, lived next door, and was a great benefit during this time. By 1838, Nancy had gained the assistance and support of her two brothers James Smith Ryall (1798-1882) and John Bacon Ryall (1804-?) whom had acquired John P. White’s land next to the Shepherd’s farm. In 1851, Nancy A. (Ryall) Shepherd finally sold the 170 acres of land in Henrico County, that she inherited from her grandfather’s estate in 1818, to her son John D. Shepherd for five dollars. Nancy died in Henrico County on July 10, 1859, of consumption.

At present, little information has been recovered pertaining to David and Nancy’s daughters; However, there is an abundance of records pertaining to their son John David Shepherd (1826-1895). In 1848, John married Cordelia E. Ford (1825-1876). They would raise eight children on the 170 acre farm upon which John was born. After the death of his first wife, John married Odora Mildred Cauthorne of Hanover County, Virginia. Together they would rear an additional five children in Henrico County. John D. Shepherd died circa 1895.

Circa May of 1827, Royal F. Shepherd’s cousin Peter Cottrell (1783-1827) died in Henrico County. Peter was the son of Peter Cottrell (1760-1815) and Susanna Shapard (1760-1807). Peter married Sarah “Sally” Ellis on November 26, 1804, in the city of Richmond, Virginia. They had seven children: Lucy, John, Maria, Sarah, Peter, Reuben and Caroline. During the War of 1812, Peter served as Sergeant in the 33rd Regiment Virginia Militia commanded by Capt. William Henley. On May 12, 1827, the Henrico County Court appointed Royal F. Shepherd, Stephen Duvall, John Bowles, Malachai Tinsley to appraise the estate of the late Peter Cottrell. His wife, Sally Cottrell, was given guardianship of the minor children.

In late 1828 or early 1829, Royal F. Shepherd’s wife gave birth to a daughter. They named her Jane Ann Shepherd (c.1829- 1895). This would be the last child born within their union.

In 1829, Royal F. Shepherd was residing in the Upper District of Henrico County, specifically in Precinct 13. Henrico County authorities had divided the county into precincts in 1823, for greater ease of land processioning and voting. Royal’s brother David A. Shepherd resided in Precinct 17. In 1829, the Henrico County personal property tax list documents that Royal F. Shepherd had five slaves. Four of the slaves were over the age of 16 years old, and one of the slaves was between the age of 12 to 16. He also had four horses.

No comments:

Post a Comment